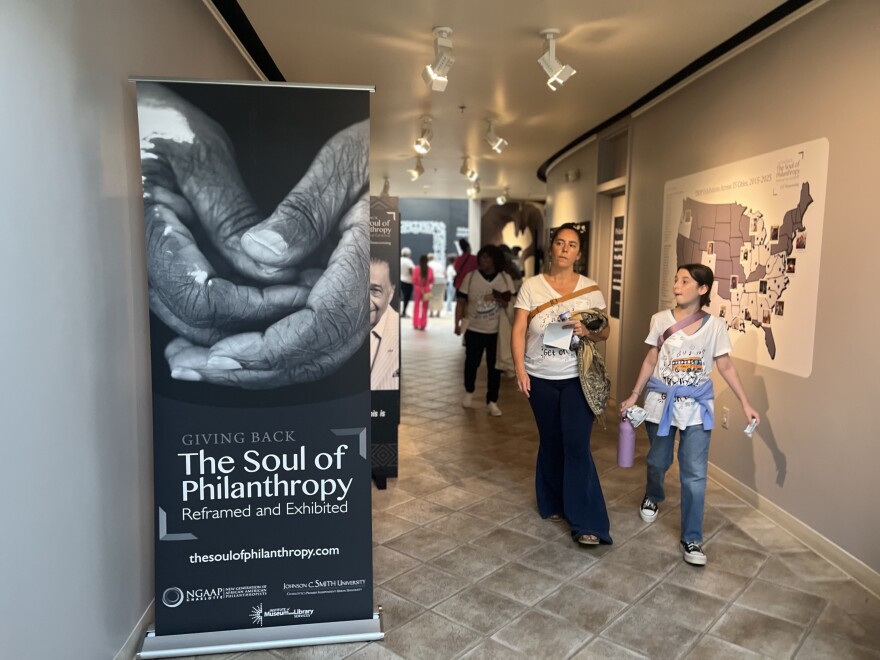

People frequently identify the phrase “philanthropy” with the wealthiest members of society, many of whom are white. A new exhibit at the Charlotte Museum of History highlights the work of Black philanthropists and attempts to redefine what philanthropy means.

At the museum, Jasmine Stowe experimented with a box containing chalk in various hues, including blue, pink, and green, on a recent afternoon. She went to a black wall and opted for white.

“Give back; our babies depend on it,” Stowe remarked.

She claims that because of her line of work, she chose to record those statements.

I teach. According to Stowe, children are vital to her. “I am aware of how critical it is to ensure students have the tools necessary for success.

On a wall with a large plaque that reads “Why I Give Back,” Stowe placed her imprint. Messages like “to ease burdens, to build the futures,” and “I love us” are emblazoned on the wall.

Another prominent image is a large poster of Sarah Stevenson. A former member of the Charlotte-Mecklenburg school board, Stevenson was Black and contributed to the development of a segregated busing strategy in the 1970s.

Charles Thomas was next to Stevenson’s photo. One of the individuals behind the display is Thomas, who works for the Knight Foundation.

People who were civil rights campaigners were the people we wanted to profile. According to Thomas, there are both well-known people and those who are contributing in what some may consider to be modest and insignificant ways. “To demonstrate that the African American community is the rightful owner of charity.

In addition to serving on the school board, Stevenson had a variety of other positions. She founded the Tuesday Morning Breakfast Forum and participated in local politics through the Black Political Caucus. Candidates for municipal office frequently use the forum to highlight the benefits they would provide to the community if elected.

Thomas cites this as one of the reasons it was crucial to highlight Stevenson’s influence. According to Thomas, it was Sarah Stevenson’s responsibility to lead our community and then return the favor by hosting a forum, gathering people, and fostering harmony.

The exhibit also includes George Davis, a well-known Charlotte schoolteacher. According to Thomas, it is crucial to draw attention to charitable endeavors that emphasize helping neighbors and volunteering.

According to Thomas, if we don’t have these stories to inspire others, we start to feel helpless, like we don’t have control, and that we can’t influence our communities the way we have for centuries.

After making its debut at Johnson C. Smith University in 2015, “Giving Back: The Soul of Philanthropy Reframed and Exhibited” has subsequently traveled to over 30 locations, including Chicago and Atlanta.

The exhibit was wandering around with Valaida Fullwood. Alongside Thomas, she has engaged with museum visitors. Visitors who were returning to the museum to view the show with Florida-based pals.

In addition to co-founding the exhibit, Fullwood is the author of “Giving Back: A Tribute to Generations of African American Philanthropists.” Thomas, a co-author, took the pictures for the book, which was released in 2011. According to Fullwood, she authored the book to alter the way that Black people are perceived in relation to philanthropy.

When Black people were included, the stories primarily focused on white givers and depicted us as needy or with our hands out. According to Fullwood, I felt obligated to relay the stories I knew.

The New Generation of African American Philanthropists was also co-founded by Fullwood. Since its founding in 2006, the group has grown to about 100 members. The organization supports Black NGOs and activities and disburses funds. Fullwood claims to have distributed more than $2 million in Charlotte since its establishment.

Fullwood cites the history of African-Americans in a nation where they have experienced deprivation as one of the reasons the exhibit and Black stories on charity are special.

of chances to be wealthy and deprive of all material belongings. Fullwood claimed that in certain cases, they even denied our humanity. As a result, we leaned into our humanity by being kind and giving in a variety of ways—that is, by taking care of one another and demonstrating love—even when we didn’t have any cash or money to donate.

Fullwood frequently likes to paraphrase an old African proverb that is on display when considering the exhibit.

This means that the hunter, Fullwood, will always be exalted in the account of the hunt until the lion shares his tale.

Fullwood thinks that visitors will take away the message.

The Charlotte Museum of History’s Soul of Philanthropy exhibit is open through October 19.