Between 1930 and the restoration of democracy in 1983, Argentina saw seven different coups, but the “Dirty War” is arguably the most notorious.

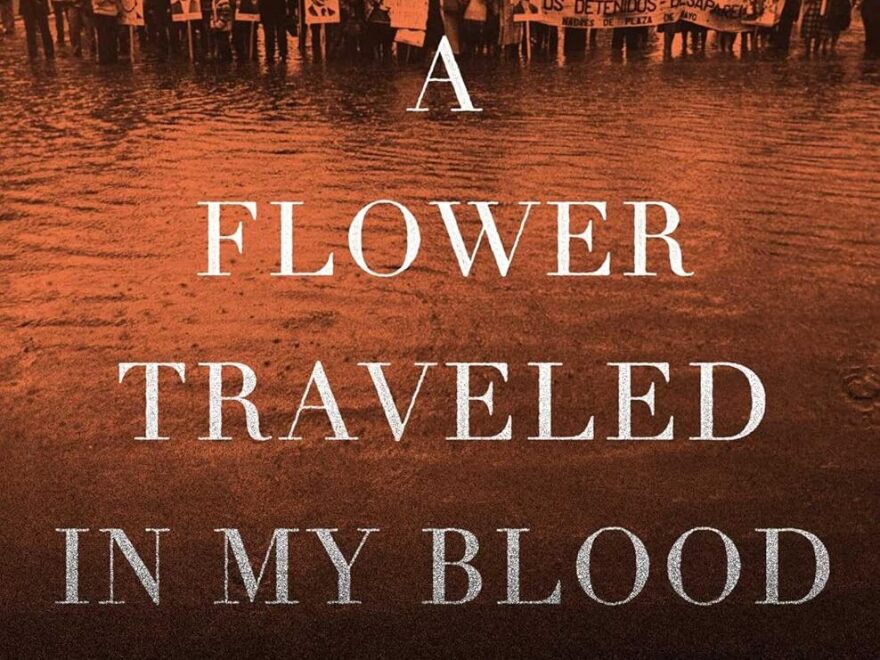

Those who were considered “subversive” were routinely murdered, tortured, and vanished by the country’s military regime during this period of ruthless repression, which lasted from 1976 to 1983. I was unaware that hundreds of pregnant women and their infants were among the missing until I read Haley Cohen Gilliland’s compelling, true story, A Flower Traveled in My Blood: The Incredible True Story of the Grandmothers Who Fought to Find a Stolen Generation of Children.

The incredible tale of the Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo (“Grandmothers of the Plaza del Mayo”), a group of brave grandmothers who spent decades looking for their kidnapped grandchildren, is told in Gilliland’s debut book (of many, we hope). The Plaza de Mayo in Buenos Aires, where the grandmothers staged weekly marches before the presidential palace to demand justice and answers, is the source of their name. Members of the same dictatorship that had vanished their parents unlawfully adopted some of their grandkids.

The main character that Gilliland focuses on is Rosa Tarlovsky de Roisinblit, whose pregnant daughter Patricia was among the missing people who vanished in 1978. In the past, Patricia and her spouse, Jose, were involved with a left-wing Peronist organization called the Montoneros. However, a large portion of the group had been slain or driven into exile by the time she was abducted. They stopped being involved since they had a small daughter and a child on the way. However, Gen. Jorge Videla, who had taken over after the 1976 coup, was unaffected by this.

“Not only militants but those on the further peripheries of the left” were the targets of Videla’s junta. Students. artists. reporters. leaders of the union. attorneys who supported unions. musicians. poets. priests who provided aid to the underprivileged. Nuns who assisted needy families in their search for missing family members. By the dictatorship’s standards, they were all’subversives,'” writes Gilliland. The National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons was founded by then-newly elected President Ra l Alfonsn following the fall of the junta. The commission’s findings listed 8,960 disappearances, but it cautioned that since the military had destroyed all pertinent data, the actual number may be greater. An estimated 22,000 Argentinians had vanished by 1978, according to a leaked report from Operation Condor, a transnational coalition of Latin American military regimes determined to eradicate “leftists, communists, and Marxists.”According to more recent estimates, the real number was close to 30,000. Although the Abuelas think the number may be as high as 500, the official count of the stolen children is 392 instead.

Gilliland skillfully captures the heartbreak and unwavering resolve of numerous other grandmothers’ real-life experiences, even though Rosa Roisinblit’s narrative serves as a throughline. In actions that put them in grave danger, these women marched, wrote letters to media and diplomats, and made appeals to religious leaders. According to Gilliland, the Abuelas were infiltrated at one point, and three of their leaders were abducted, killed, and thrown from an aircraft, exactly like so many of their daughters who vanished after being kept alive for just long enough to give birth.

Nevertheless, the Abuelas persisted, coming up with creative ways to carry on their hunt. They pretended to be “saleswomen promoting a new baby product,” went for “pedicures to extract information from salon owners who had also polished the toenails of suspected kidnappers,” gathered intelligence by posing as mourners at cemeteries, and passed information at fictitious birthday parties at cafes (where large groups attracted less suspicion). In one instance, a grandma planned to be admitted to a mental health facility in order to obtain information.

Gilliland’s work would have been a significant accomplishment even if she had only written about the Abuelas’ real-life experiences. As she explains, however, “Kissinger backed the assassination of a prominent Chilean general in hopes of facilitating a military takeover of socialist president Salvador Allende.” She goes further, taking the reader through Argentina’s complicated political history and shedding light on the numerous ways the United States was complicit in Argentina and beyond.

Even though Videla’s junta brutalized its own people, there is still hope in A Flower Traveled in My Blood. The geneticist Mary-Claire King, who helped the women use DNA in their search after discovering that breast cancer is inheritable, was the result of the Abuelas’ quest. “King herself posits that she and the Abuelas were among the pioneers of genetic genealogy,” according to Gilliland. In the end, their efforts lead to the discovery of dozens of grandkids.

Although regrettable, it makes sense that some of these reunions led to more issues. In several instances, devoted families who thought the children had been abandoned had adopted them. Some refused to submit DNA to verify their ancestry.

It’s difficult to view the Abuelas and their achievements as anything other than inspirational, though. In order to defend their family, grandmothers banded together across social boundaries and occasionally found hidden sources of strength. The Abuelas are still united in their fight today, and Gillibrand does a fantastic job of telling their remarkable tale. According to the writer, “The Plaza de Mayo seemed to take individual grief and transform it into collective determination.” I can’t think of anything more striking than that as evidence of resistance and unity.

Copyright 2025 NPR