We’re celebrating ten years of Our Rich History. You can browse and read any of the past columns, from the present all the way back to our start on May 6, 2015, at our newly updated database:

nkytribune.com/our-rich-history

By Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD

Special to NKyTribune

On June 14, 1775, the Second Continental Congress established the Continental Army, marking the official beginning of the US Army. With the assistance of the French and the Spanish, the American forces defeated those of the powerful British Empire in the American War for Independence — also called the American Revolutionary War (“

The U.S. Army: America’s First National Institution

,” timeline).

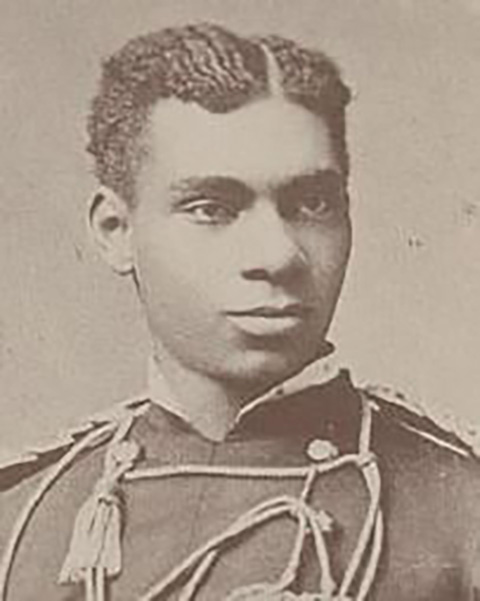

Exactly 102 years later –on June 14, 1877 — Henry O. Flipper (1856–1940), born into slavery in Thomasville, Georgia, became the first Black to graduate from the prestigious West Point Academy. He received his diploma from Ohio native, General William Tecumseh Sherman (1820–1891). It was a time of segregation and overt racism. Of his days at West Point, Flipper wrote: “There was no society for me to enjoy — no friends, male or female, for me to visit, or with whom I could have any social intercourse so absolute was my isolation” (“

Henry O. Flipper

,” Charles Young Buffalo Soldiers National Monument, National Park Service; Lowell D. Black and Sara H. Black, An Officer and a Gentleman: The Military Career of Lieutenant Henry O. Flipper. Dayton, Ohio: Lora, 1985; “

Henry O. Flipper

,” New Georgia Encyclopedia.)

As a second lieutenant, Henry O. Flipper served with the African-American 10th Cavalry, part of the “Buffalo Soldiers” regiments (so named by American Indians against whom they fought) at Fort Sill in Oklahoma. There, he “proved a capable engineer, building roads and telegraph lines from Gainesville, Texas to Fort Sill,” as well as a drainage system to combat malaria “known as ‘Flipper’s Ditch,’ ” that is a registered National Historic Landmark (“

Biographies: Henry Flipper

,” The National Museum of the United States Army).

Henry Flipper is remembered at the Charles Young Buffalo Soldiers National Monument in Wilberforce, Ohio. Young was the third Black to graduate from West Point. Born into slavery in May’s Lick (Mayslick), Kentucky, Charles Young (1864–1922) fled with his parents across the Ohio River to Ripley, Ohio, a center of abolitionism. There, he graduated from the city’s integrated high school and taught for two years at Ripley’s Black elementary school. Admitted to West Point in 1884, he graduated in 1889. At West Point, Young experienced the same racism and isolationism that had plagued Henry Flipper.

Second Lieutenant Young served with the 9th Cavalry African-American Buffalo Soldiers in Nebraska and Utah, being promoted to captain. In 1894 Young was appointed the head of the new Military Sciences & Tactics program at Ohio’s historically Wilberforce University, where he helped to establish the university’s marching band and became friends with fellow professor W.E.B. Dubois. In 1907 he purchased a house in Wilberforce that he affectionately called “Youngsholm (

A Triumph of Tragedy: The Life of Charles Young

, introductory film at the Charles Young Buffalo Soldiers National Monument; “

Brigadier General Charles Young

,” Charles Young Buffalo Soldiers National Monument, National Park Service).

In the summer of 1903, Charles Young became the “first African-American national park Superintendent,” serving at Sequoia National Park in California. In the following year, 1904, he married Ada Barr (1880–1953). The couple would eventually have two children, Charles Noel Young (1906–1967) and Marie Young (1909–1970). In the same year, Young was appointed military attaché to Haiti and the Dominican Republic, and from 1912 until 1916, to Liberia in Africa. In 1916 he “distinguished himself at the Battle of Agua Caliente” against Pancho Villa in Mexico (Jack Wessling, “Young, Charles Denton, Colonel,” in Paul A. Tenkotte and James C. Claypool, The Encyclopedia of Northern Kentucky, 2009; “

Brigadier General Charles Young

,” Charles Young Buffalo Soldiers National Monument, National Park Service; “

Charles Young’s Family

,” Charles Young Buffalo Soldiers National Monument, National Park Service).

Promoted to major in 1912, to lieutenant colonel in 1916, and to colonel in 1917, Young was given a medical retirement in 1917 but continued to train Blacks for service in World War I. In 1920 he returned to Liberia as a military attaché, and on a visit to Nigeria, became ill and died in 1922. Eventually, his body was sent back to the United States, where he was buried with military honors at Arlington National Cemetery. In 2021, Young was elevated posthumously to Brigadier General.

The story of Charles Young is one of immense fortitude and persistence in a time period where racism, segregation, and inequity ruled. In his biography entitled Black Cadet in a White Bastion: Charles Young at West Point, Brian G. Shellum states that Young was the last Black to graduate from West Point for nearly half a century: “The end of nominations of blacks to the academy coincided with the end of Reconstruction and the beginning of the enactment of Jim Crow laws that codified segregation and discrimination. After Young, no other African American gained admittance to West Point until after World War I, and no African American graduated from the academy until Benjamin O. Davis Jr. did so in 1936” (Brian G. Shellum, Black Cadet in a White Bastion: Charles Young at West Point. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2006).

Paul A. Tenkotte, PhD is Editor of the “Our Rich History” weekly series and Professor of History at Northern Kentucky University (NKU). To browse ten years of past columns, see:

nkytribune.com/our-rich-history

. Tenkotte also serves as Director of the

ORVILLE Project

(Ohio River Valley Innovation Library and Learning Engagement). He can be contacted at

.