James Farrell’s weekly education email was the first to publish this.To receive it in your inbox first, sign up here.

A recent study is once again emphasizing how challenging it has been for students to recover from the coronavirus outbreak.

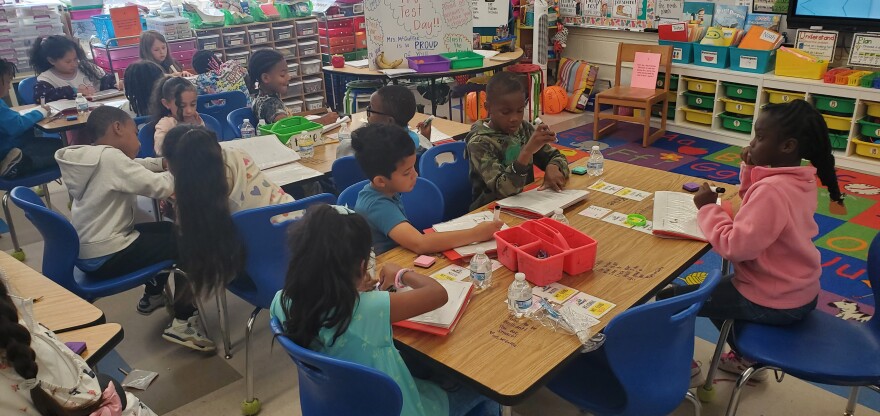

Parents of students attending Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools should be fairly familiar with Curriculum Associates, the company that created the adaptive learning platform i-Ready, which CMS employs to identify students’ academic strengths and shortcomings.

They use data from i-Ready to examine reading and math testing patterns for around 14 million K–8 pupils nationwide. We may examine this report from two perspectives: what it says about national accomplishment and what it shows about various student subgroups.

According to Curriculum Associates’ head of measurement, Kristen Huff, the general conclusion about the former point is as follows: Since the pandemic, we have plateaued. Students are finding it extremely difficult to return to their pre-pandemic status as a result of this.

According to Huff, one encouraging aspect is that students are indeed learning. They are learning at roughly the same pace as they did in the past. That rate, however, must quicken to catch up.

Examine the following charts from the report. The top one displays the proportion of pupils in each reading grade who achieved grade-level competency between 2019 and 2024. For math, the lower one displays the same. Therefore, you may use the small trend line that joins the top of the bars to track each grade’s historical performance in each topic.

You may note right now that all but four categories continue to score lower than they did in 2019. The reading grades of grades 5-8 are the four exceptions, but there may not be much to rejoice about. Even before the pandemic, the percentage of pupils in those grades performing at grade level was low; in 2019, less than 50% of children in those grades were performing at grade level. Additionally, since 2019, all of those scores have essentially stayed the same.

That brings to mind a discussion I had while covering this article on the difficulties in raising reading scores with Dennis Davis, an early literacy education professor at NC State. I had questioned him about how concerning post-pandemic reading results should be. He informed me that it’s both normal and a catastrophe, indicating that reading has historically been a problem in the country, even before COVID-19.

He informed me that these difficulties have existed for a while.

You may also see that the lines in those figures become flat following the sharp declines in 2020. That illustrates the sluggish pace of progress Huff was mentioning.

There are a few minor indications of progress, especially in arithmetic in grades 4–8. After a few years of no change, the report observes that this rising trend, however modest, is encouraging.

Younger students

even those who were toddlers during COVID

are struggling the most

But when you look at those charts, you’ll notice something else as well: Since COVID-19, younger students seem to be having the most difficulty.

Students in grades K–3 continue to perform below grade level in reading and arithmetic at rates significantly lower than their peers prior to the epidemic. Those holes appear to be most noticeable there.

That’s odd, as Huff informed me, because those K–3 youngsters were not even enrolled in school when the pandemic struck. Additionally, Huff informed me that this is not the first time we have seen evidence indicating this. In another study conducted last year, Curriculum Associates came to a similar conclusion.

According to Huff, we were quite worried about the students who were enrolled in classes and how the closures were interfering with their education. During the pandemic, I didn’t really think to worry as much about children or future pupils who were just, say, two, three, or four years old. However, the research also indicates that their learning and development were affected.

Achievement gaps persist

A significant worry that we have observed elsewhere is further supported by the report: the gap between high- and low-achieving kids is widening. It’s an indication that struggling pupils are finding it challenging to acquire the support they require.

When the Department of Education announced the results of its National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) exam in January, that was one of the news stories.

According to the survey, high-achieving students—those who fall into the 90th percentile, for example—have been able to maintain or even surpass their academic performance during the pandemic. However, results for kids in the 10th percentile have been steadily declining. Additionally, the research observes that the gap between results in the 75th and 25th percentiles keeps widening.

According to Huff, it demonstrates the necessity of directing resources where they are most needed.

The number of kids at majority Black schools who achieve grade-level competency has steadily increased in almost every topic and at every grade, which is encouraging when it comes to evaluating performance gaps. This occurs along with a little decline in test scores at predominantly white schools.

However, that is insufficient to bridge the historical divide between those two subgroups. For example, the percentage of pupils in mainly Black schools who are proficient at grade level in reading has increased from 35.6% to 39.3%. At schools with a majority of white students, that percentage decreased by one percentage point, but it was still higher at 55.6%.

What comes next?

In the upcoming weeks, a few more significant performance indicators will be released.

The next wave of NAEP results will be released later this year. These scores will concentrate on reading and math from the 12th grade as well as science from the 8th grade.

Additionally, test results and school performance information for the 2024–2025 academic year will be made public by the Department of Public Instruction. Usually, that is released around September.

These local data will be especially crucial since they will demonstrate how successfully CMS met its academic objectives, which center on demonstrating gains in math and reading.